Vesting of performance-based stock:

Observations on the use of the Matlack formula

Frank van Lint, Daan Staffhorst, Stijn van Lint – Dellin Investments, June 2025

Synopsis

The Matlack formula is used in the search fund space to calculate how much performance-based stock vests in case of hold periods longer than 5 years. It is useful in specific situations where one single investment is made by investors and one single distribution is received by investors at exit. In practice, however, investors and searchers increasingly deal with partial sales, distributions, recaps, additional capital investments etc. The Matlack formula, which is based on MOICs, then becomes less useful. Without giving up on the economic standard set by the Matlack formula for vesting, we suggest an IRR based methodology that can be applied in all situations. This methodology can serve as guidance for investors, boards and searchers on how to address the vesting of performance-based stock. We would like to thank Tom Matlack for providing his comments.

1. Introduction

The model for traditional or classic search fund investing provides for vesting of common stock by a searcher/operator as follows:

· 8.33% of common stock at acquisition close

· 8.33% of time-based common stock whereby every month 1/48 is vested if the searcher/operator is still working as CEO of the acquired business (“time-based vesting”)

· 8.33% of common stock based to the extent preferred investors realize a minimum IRR (“IRR-based vesting” or “performance-based vesting”). Generally, common stock is earned based on the return percentage generated by investors with a minimum threshold of 20% and capped at 35% IRR.

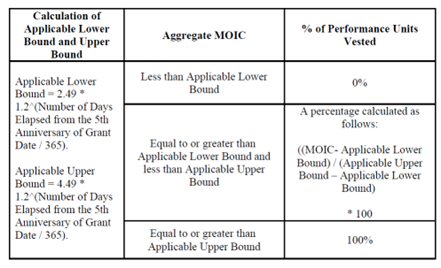

It is important to emphasize that this approach for performance-based vesting does not consider the hold period. It is hard to maintain a high IRR over a long period of time. That could motivate the searcher/operator to exit earlier to maximize the vesting of performance-based common stock. This could be the opposite of what investors want. They want to deploy capital in successful businesses. To balance the interests of searchers and investors, Tom Matlack suggested that after 5 years the IRR-based vesting method is to be replaced by vesting tied to a realized MOIC for investors: “After the fifth anniversary, the cash-on-cash goal posts do not remain static. They continue to compound until the eventual exit, whenever that is, at an annual rate that no longer requires the 35% pace to max out”. In addition, he suggests: “reverting to the minimum of 20% per annum as the standard not just for the bottom of the range after the fifth anniversary but across the board. This recognizes the fact that a business that has grown shareholder for value for 35% per year for 5 years and then continues to compound that capital gain at 20% per year thereafter is still going to be a home run by any standard.” This has resulted in the adoption of the “Matlack formula” whereby the vesting threshold after year 5 is expressed as a MOIC based on said IRR. In operating agreements this is usually described as follows:

Let’s take an example to demonstrate how this formula works out. A company is sold after 8 years and investors realize a MOIC of 6.5x. The formula provides that the searcher vests 100% of the performance-based stock if the MOIC for investors is at least: 4.49 x 1.2^3 = 7.76. This equals an IRR of 35% over a period of 5 years plus and IRR of 20% over a period of 3 years. In this example the searcher vests 63.50% ((6.5-2.49x1.2^3)/(4.49x1.2^3 -2.49x1.2^3) x 100%) of the performance-based stock.

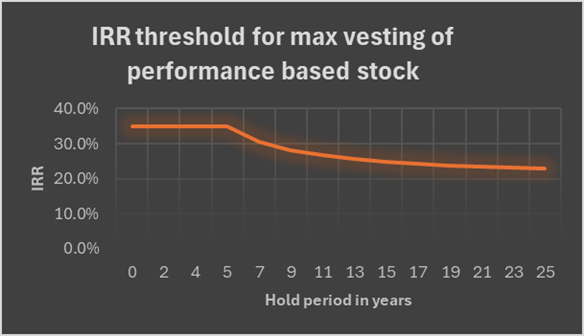

The Matlack formula implies that the IRR threshold for vesting reduces as the hold period becomes longer. It requires 35% IRR over a hold period of 5 years, but the required IRR drops if the investment is held for a longer period because the threshold IRR for additional years is 20% per year. The (average) IRR and applicable upper bound to vest all performance-based stock therefore declines from 35% at the end of year 5, to 24.8% in the case of a hold period of 15 years, and approaches 20% for a very long hold period. The following schedule shows this declining investor IRR threshold for maximum vesting of performance-based stock.

2. Situations where the Matlack formula does not work well

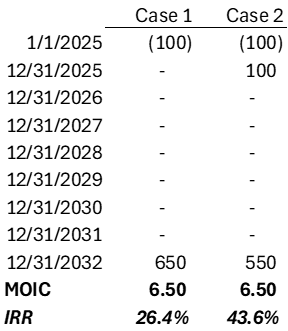

The Matlack formula assumes one single investment and one single payment at exit. However, in practice there are many situations where the use of a MOIC-based approach becomes a problem. Let’s compare the following two cases:

In both cases the investors invest 100 and realize a MOIC of 6.5x after 8 years. As mentioned above, the Matlack formula provides that 63.50% of performance-based stock is vested in both cases because the realized MOIC is the same. However, in the second example where investors received a distribution at the end of the first year, the realized IRR for investors is much higher. The switch from IRR to a MOIC is punitive for the searcher in case 2.

Similar consequences are seen when part of the company is sold, and the remaining part is sold a few years later. The investor’s advantage of the early (partial) exit is not considered when calculating the MOIC. Because the Matlack formula connects to one single amount invested, a similar problem also arises when capital is called multiple times (for example under a committed capital arrangement or capital calls for tuck in acquisitions).

3. Time to return from MOIC to IRR?

For the first 5 years, the performance requirements are expressed as an IRR percentage. After five years, the Matlack formula switches to using MOICs (but in essence the Matlack formula remains IRR based: 35% IRR for the first five years and 20% for the remaining hold period!). Since the use of a MOIC is limiting the usefulness of the Matlack formula in many cases, it would be a big advantage to express the performance targets based on IRR.

As mentioned above in paragraph 2, using a MOIC is in many cases not an appropriate method to determine investor return. The investor IRR is a better method because it considers the time factor and can thus be used in case additional capital is invested, when distributions are received during the hold period, etc.

If investor return is expressed as IRR, and the performance targets are expressed as IRR, then we can compare apples with apples and calculate the vesting percentage of performance-based stock.

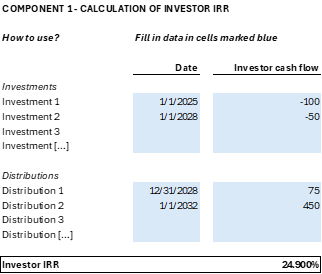

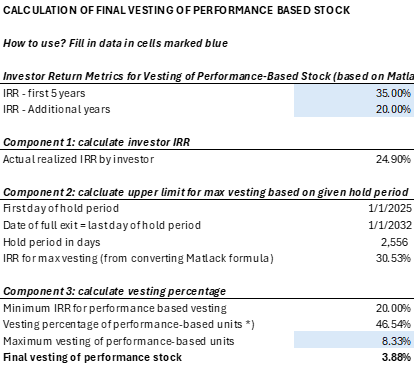

It is easy to determine the actual realized investor IRR by tracking the exact moments when investors made their investment(s), and when distributions or exit proceeds are received. With this information, the XIRR function in Excel is a great tool to calculate the exact IRR for investors. The Excel model that we made shows the following example.

If we know the IRR for investors, the next step would be to calculate the vesting percentage of performance-based stock. As mentioned above, the Matlack formula implies that the (upper) IRR limit for full vesting reduces the longer the hold period. The Excel model includes a sheet to calculate the IRR upper limit given a any hold period. As the lower limit is 20%, we can extrapolate the percentage of stock that vests when the investor IRR is between 20% and the upper limit. The Excel model that we use shows in this example the following.

*) (24.90% - 20.00%) / (30.53% - 20.00%) = 46.54%

4. The hold period

Another important aspect to determine the IRR is the hold period. We define it as the period between the date of the first investment of capital (to fund the acquisition) and the date the last payment is received by investors.

This implies that an exit with a seller’s note extends the hold period until the seller’s note is paid and the cash is distributed to investors. In other words, investor IRR is calculated on a cash-on-cash basis regardless of whether the nature of the underlying incoming payment is, for example, a partial sales proceed, a distribution, a repayment of capital, an earn-out payment, interest on a seller’s note, or payment of principal of a seller’s note.

If an exit is structured via a merger and the sellers are paid in shares of another entity, we believe the value of new shares on the closing date should be considered to be payment in cash. The difference in treatment between payment in shares and payment with a seller’s note is the seller’s note is a deferred payment in cash for selling the investment. If the note and/or interest are not collected, it will not count towards the return on investment for the investor when calculating investor IRR. When the payment is received, it will count towards investor IRR.

Payment in shares of another company could generate returns (up and down) for which the searcher/operator is no longer responsible. This would justify considering only the value of these new shares as exit proceeds at the time of receipt of these shares. Future changes in the value of these new shares do not account towards investor IRR.

5. The “new Matlack formula”

Very recently, Tom Matlack therefore suggested replacing the original formula with a new formula:

“I propose to codify the way we discuss outcomes in the performance equity component of Search Entrepreneurs' compensation as follows: 3.0x MOIC would receive 20% of the performance equity, 3.5x MOIC would receive 40%, 4.0x MOIC would receive 60%, 4.5x MOIC would receive 80%, and 5.0x or over would receive all the performance equity available—linear interpolation between these points. In addition to the above MOIC measure, to receive any performance equity, the Search Entrepreneur would need to achieve a minimum of 20% IRR through the final exit of the investment.”

Although this new formula seems simple to use, it does raise several important questions.

First, the first metric he uses is MOIC to determine the percentage of vesting. A low MOIC implies less vesting and a high MOIC implies higher or full vesting. There is some logic to that but when you look deeper, it is not a good metric to measure performance because it simply does not take the hold period into account. A MOIC of 3x can generate a higher IRR for investors than a MOIC of 5x.

Second, the MOIC approach still does not work well in certain situations, for example when capital is called/invested two or more times.

Third, if you do the math and apply this new formula to a standard waterfall, then the duration of the hold period can lead to distorted outcomes in our view. For example, in a situation where a deal generates a 5x (deal) MOIC in combination with a 7-year and 8 months hold period, then with the application of a standard waterfall (8% coupon, 1x liquidation preference) the searcher would vest all common stock because he would meet the 5x MOIC and the minimum IRR threshold of 20%. If in that same example, the hold period is 8 years and 3 months (the hold period is only 7 months longer), then the 20% IRR for investors is not met and there is no vesting of performance-based stock. A slightly longer period can thus have major consequences for vesting.

To avoid these kinds of consequences, we still believe that an IRR based method is the best way to measure performance. It is not complicated (actually very simple) to do that with the Excel model we made. We stress that in this article we do not comment on what IRR should be to (fully) vest and have simply adapted to economic terms underlying the original Matlack formula to create a model fully based on IRR given any hold period. It also provides for a possibility to adjust the bandwidth of the 20%-35% IRR vesting range.

6. Final remarks

The investor IRR is positively affected by additional distributions later in time (for example following the receipt of an earn-out payment). A higher investor IRR would also affect the vesting percentage for the searcher. We suggest that the possibility of a higher vesting percentage (because of a sellers’ note, earn out, etc.) is not considered until it becomes a reality. In other words, only when additional cash is received, the vesting percentage is re-calculated and a catch-up for the searcher will be paid at that same time. The additional cash is sufficient per definition to make the catch-up payment.

This article does not deal with the question of which distributions are considered to count towards investor IRR. Especially this concerns tax distributions. We will not elaborate on this here but plan to address that topic in another article.

We would like to stress that (performance-based) vesting of stock is just one element of a searcher’s compensation package. Other elements like salary, bonus, and severance are part of that as well. It is up to the board to arrive at a balanced compensation structure. Changing circumstances can be a good reason to change the compensation structure. That could also apply to the element of performance-based vesting. The board has an important role in balancing interests of investors and searchers, and we hope that this article helps to navigate that in a good way.

The underlying Excel model is available upon request (frank@dellininvestments.com or daan@dellininvestments.com).